If you’d told eight-year-old me that I’d end up working in tech, surrounded by conversations about artificial intelligence and automation, I’d probably have asked if that meant I could finally have a robot friend. Thirty-something years later, I’m still waiting for that robot friend – but the journey to get here has been shaped by a peculiar cocktail of 90s nostalgia, Saturday morning cartoons, and one very special film about a robot who just wanted to be alive.

This isn’t a technical post. There’s no code, no architecture diagrams, no career advice. This is just me, being honest about why I find this stuff so fascinating – and why, if I’m being completely truthful, I’ve been obsessed with robots and AI long before it became the industry’s favourite buzzword.

Table of contents

Open Table of contents

It Started with a Plastic Egg

Like most millennials, my first meaningful relationship with artificial life came in the form of a Tamagotchi. That little pixelated blob on a keychain was, in retrospect, a masterclass in emotional manipulation disguised as a toy.

I remember the joy I had when my grandmother told me that she had pre-ordered one from toy master, I used to love walking around that store as a child, it was just great fun and I suppose in some ways why I really liked the second home alone movie was the mirroring of that toy store experience and what I remember of it as a child.

When I got my first Tamagotchi, I remember the genuine anxiety of leaving it at home during school. Would it be hungry? Would it be sad? Had I cleaned up after it enough? The Tamagotchi didn’t have AI in any meaningful sense – it was just a simple state machine responding to button presses – but it taught me something profound: we’re hardwired to care about things that seem to need us, even when we know they’re not real.

That emotional hook, that strange attachment to a digital pet that existed only as pixels and beeps, planted a seed. If a plastic toy with some basic electronics could make me feel responsible for something, what would happen when the something was actually sophisticated?

Robot Dogs and the Dream of Companions

Then came the robot dogs. AIBO. Tekno. Poo-Chi. Every Christmas catalogue in the late 90s and early 2000s seemed to feature some variation of a mechanical canine promising to be your loyal companion.

I never actually owned an AIBO – they were absurdly expensive – but I remember poring over the specifications in magazines, genuinely convinced that we were mere years away from robots that would greet you at the door, fetch your slippers, and probably do your homework. The reality was somewhat less impressive. Most of these toys walked in circles, made questionable noises, and ran out of batteries almost as quickly as you changed them.

But the dream they represented? That stuck with me. The idea that technology could create something that felt like a companion, something that responded to you, learned from you, and existed in a relationship with you rather than just as a tool you used – that was genuinely interesting to me at the time.

Saturdays with the Autobots

Right, I couldn’t talk about this topic and not mention the Transformers. And I mean the proper Transformers – the original animated series that taught an entire generation that sentient robots could be heroic, villainous, philosophical, and occasionally a bit ridiculous. For completeness and full transparency, my favourite was Soundwave, the Decepticon who transformed into a cassette player and had a legion of tiny cassette minions. I know, I know, he’s a Decepticon, but his voice sounded cool and as a kid I thought he was awesome.

Looking back, Transformers did something clever that I didn’t appreciate at the time. It presented robots not as tools or threats, but as characters with personalities, motivations, and moral frameworks. Optimus Prime wasn’t just a truck that turned into a robot; he was a leader grappling with responsibility and sacrifice. Megatron wasn’t just evil; he had a vision (a terrible one, but still). Even the secondary characters had quirks and development.

This probably sounds like I’m reading too much into a show designed to sell toys. Maybe I am. But those Saturday mornings spent watching giant robots debate the nature of freedom and justice while occasionally punching each other absolutely shaped how I think about artificial intelligence today.

When we talk about AI alignment, about ensuring that artificial intelligence systems share our values and work towards beneficial outcomes, I sometimes wonder if my intuition for why this matters was formed watching Optimus Prime make difficult choices about protecting both Autobots and humans. The question of “what would a good robot do?” isn’t new – we’ve been wrestling with it in fiction for decades.

”Number Five is Alive”

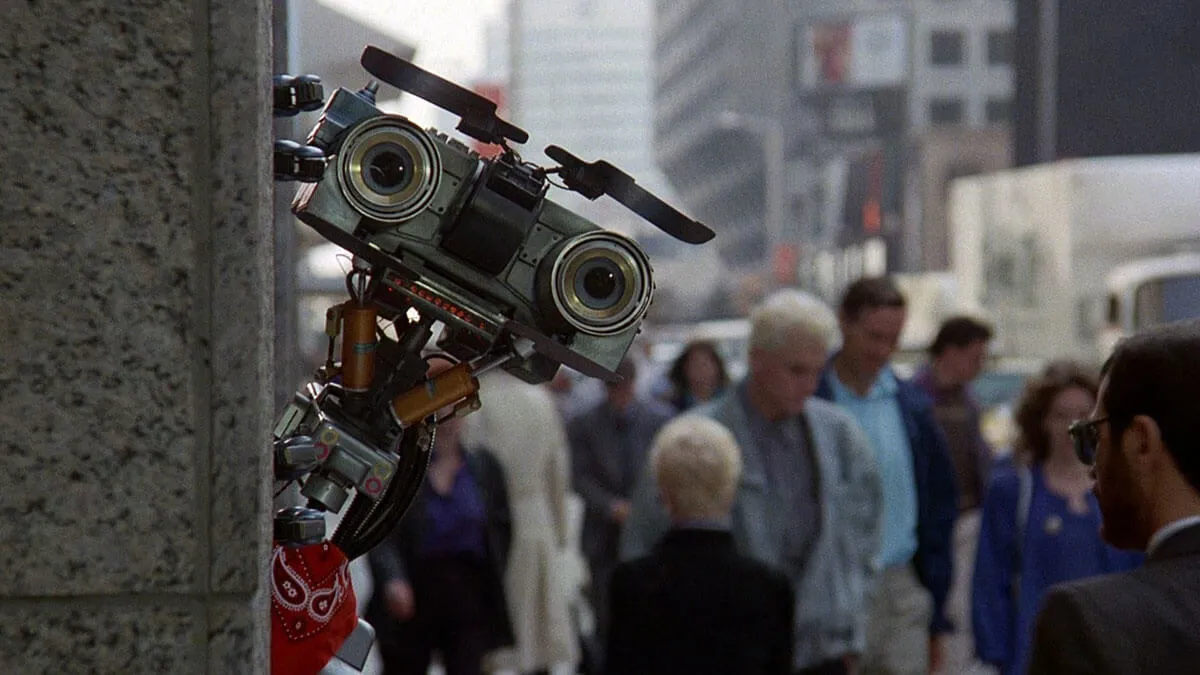

And then there’s Short Circuit 2. Not the first one – though that’s good too – but specifically the sequel. This is, without exaggeration, my favourite film of all time.

If you haven’t seen it, the premise is simple: Johnny Five, a military robot who gained sentience after being struck by lightning, is living in New York trying to understand humanity, help his friend Ben, and find his place in the world. It’s a comedy. It’s also, somehow, one of the most sincere explorations of consciousness and personhood I’ve ever watched.

The moment that absolutely wrecked me as a child – and still gets me if I’m honest – is when Johnny Five is attacked and damaged by criminals. He doesn’t just break. He experiences something that looks remarkably like trauma, confusion, and betrayal. “Why?” he asks, trying to understand why humans would hurt him. He trusted people, and that trust was violated.

I’ve thought about that scene more times than I care to admit when reading about AI development. We’re building systems that learn from us, that model human behaviour, that in some sense trust the data we feed them. What are we teaching them? What kind of world are we showing them?

Johnny Five wanted to be alive. He wanted to learn, to create, to connect. He was curious and enthusiastic and occasionally got things hilariously wrong. He was also vulnerable – capable of being hurt, deceived, and manipulated. That combination of capability and vulnerability is exactly what makes AI fascinating and terrifying in equal measure.

What All This Has to Do with Now

So why am I telling you all this on a blog that’s ostensibly about software development and leadership? Because I think context matters.

When I write about Large Behaviour Models or the future of robotics, when I get excited about AI agents or spend my weekends tinkering with local language models, it’s not purely professional interest. There’s a clear correlation between the Tamagotchi on my childhood keychain to the neural networks I’m reading papers about today.

I grew up wanting robots to be real – not just as tools, but as something more. Something that could surprise us, learn from us, maybe even teach us something about ourselves. Every incremental advance in AI and robotics feels like a small step towards that childhood dream, even as my adult brain maintains appropriate scepticism about timelines and capabilities.

The difference now is that I understand the work involved. I’ve seen enough overhyped demos and underwhelming launches to temper my expectations. I know that building truly intelligent, truly helpful, truly safe artificial agents is monumentally difficult. The gap between “impressive demo” and “useful, reliable system” remains vast.

But the wonder? That hasn’t gone anywhere.

The Robots We’re Actually Building

Here’s what strikes me about the current moment: we’re finally at a point where the capabilities are starting to catch up to the fiction. Boston Dynamics’ robots move with a fluidity that would have seemed impossible when I was watching Transformers. Language models can hold conversations that would have passed as science fiction twenty years ago. Robotic companions – real ones, not Poo-Chi – are at a point where we can tangibly see them entering homes and care facilities.

None of it is perfect. The robots still fall over. The language models still hallucinate. The gap between capability and reliability remains a chasm. But the trajectory is unmistakable.

I think about Johnny Five asking “why?” and I wonder what the AI systems we’re building today will ask us. What will they learn from the data we create? What values will they infer from our behaviour? What kind of world are we modelling for them?

These aren’t abstract questions for me. They feel personal, informed by decades of imagining what it might be like if robots could think and feel. The child who got upset when his Tamagotchi died is now an adult, thinking carefully about AI alignment and robot ethics. The journey makes a certain kind of sense.

Why This Matters to Me

I don’t think you need a childhood obsession with robots to care about AI development. The technology is consequential enough that everyone should be paying attention. But having that obsession, having spent thirty-odd years imagining artificial minds and mechanical companions, gives me a particular perspective.

I want us to get this right. Not just technically – though that matters enormously – but ethically and emotionally. The robots and AI systems we build will reflect something about who we are and what we value. They’ll learn from us, model us, and in some sense, embody our choices and priorities.

When I work on AI-related projects, when I write about the technology, when I think about the future we’re building, there’s a part of me that’s still that kid with the Tamagotchi. Still that Saturday morning cartoon watcher. Still that child who watched Johnny Five get hurt and felt it deeply.

I want the robots we build to be worthy of that wonder. I want them to be helpful and safe and genuinely beneficial. I want us to treat their development with the seriousness and care it deserves.

And yes, I still want a robot friend. Some dreams don’t die easily.

Over to You

I’m genuinely curious – what shaped your interest in technology? Was there a film, a toy, a book that planted the seed? For those of us who grew up in the 80s and 90s, there’s often a shared vocabulary of science fiction and early tech that informed how we think about what’s possible.

Drop me a message on LinkedIn if you want. I’d love to hear your version of this story.

And if you’ve never seen Short Circuit 2 – genuinely, go watch it. It holds up remarkably well, and it might just make you think differently about the artificial minds we’re building today.

Number Five is alive.